Space intellectual property sits under some pretty unique legal frameworks, and they’re nothing like the ones we use on Earth. These frameworks cover patents for spacecraft tech, copyrights for space-related material, and trademarks for aerospace brands.

The space industry constantly wrestles with protecting innovations. Jurisdictional headaches and enforcement issues outside Earth’s boundaries make things way more complicated than you’d expect. You can read more about these jurisdictional complexities.

Space intellectual property faces a whole different set of jurisdictional challenges than what we see with terrestrial IP. When a spacecraft launches from the US but operates in the international waters of space, figuring out which country’s IP laws matter gets messy fast.

The Outer Space Treaty from 1967 made it clear: no country can own celestial bodies. That leaves some serious gaps in IP protection, since regular territorial laws just don’t reach into space.

Some key differences:

Space technologies often come from international partnerships—think NASA, SpaceX, Blue Origin, and other agencies working together. These collaborations need specialized licensing that considers all those overlapping jurisdictions.

Patent enforcement gets tricky when infringement happens on a spacecraft or station. Courts on Earth don’t really have clear power over what happens in orbit or on the Moon.

Patents protect core space technologies like propulsion systems, satellite designs, and life support gear. SpaceX holds a bunch of patents for their reusable rockets, which really changed the game on launch costs.

Blue Origin also protects its rocket engines and spacecraft designs with patents. Virgin Galactic keeps its suborbital tourism systems and safety tech under IP lock and key, giving it an edge in the commercial space tourism race.

Copyrights cover things like educational content, mission docs, and multimedia. NASA licenses thousands of images and videos, and keeps copyright control over research and publications.

Trademarks are how aerospace companies set themselves apart as the space tourism and satellite markets explode. Brand protection is a big deal as more players jump in.

Space mining is starting to bring new IP headaches. Companies developing asteroid mining tech need protection in multiple jurisdictions, since their activities can be far from Earth.

Space Object Registration forms the main legal link between space activities and Earth-based IP laws. The country that registers a spacecraft usually keeps legal jurisdiction over IP tied to that vehicle.

Flag State Jurisdiction borrows from maritime law. The country launching or registering a spacecraft generally keeps legal authority over IP disputes for that object.

Patent prosecution in space takes some careful thinking about where inventions get created, developed, and first used. If someone invents something on the International Space Station, multiple national patent systems might get involved.

Prior art searches for space tech are tougher, since relevant inventions might be scattered across different national databases and classification systems.

Licensing frameworks have to handle the international partnerships that are so common in space missions. Sharing tech across borders means sorting out agreements that work under several regulatory systems at once.

Enforcement mechanisms are limited compared to what we see on Earth. Space activities often lack clear legal options if someone violates IP rights, which makes investing in innovation a bit riskier.

Space intellectual property lives inside a tangled web of international treaties and national laws. This setup creates both opportunities and headaches for commercial space ventures.

The Outer Space Treaty from 1967 lays out the basics, but each country still builds its own patent and trademark rules for space.

The Outer Space Treaty from 1967 stands as the backbone of international space law. It says no nation can claim a celestial body, but it doesn’t really touch on intellectual property rights.

The treaty lays down some big principles. Space belongs to everyone. Nations stay responsible for their own space activities, even when private companies do the work.

Other agreements add to this. The Moon Agreement from 1984 talks about resource extraction but not many countries have signed it. The Liability Convention from 1972 sets up who pays for damages.

These treaties leave gaps in IP protection. They care more about territory than innovation rights, and today’s space business needs way clearer IP rules.

The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) tries to help interpret these treaties. They offer guidance on how the old agreements might apply to new commercial stuff happening in space.

International space law sets the ground rules for how space IP works. Customary international law and treaties between countries shape the system.

Patent rights usually follow the nationality of the spacecraft or the launching country. So, a US-registered spacecraft mostly sticks to US patent law. Copyright protections for space content run into similar jurisdiction questions.

International cooperation agreements often add IP rules. The International Space Station partnership is a good example of how countries can share tech but still protect their own innovations.

Some key ideas: nobody can own celestial bodies, and space should stay peaceful. These ideas shape how people can use IP rights in space.

Trade secrets are tough to keep in space. The team effort behind many missions makes confidentiality a real challenge.

The United States leads with several key laws on space IP. The Commercial Space Launch Act sets the stage for private space activities. The US Space Act encourages private development and touches on resource rights.

Major US Space IP Laws:

Other countries have their own approaches. The European Space Agency makes multinational IP sharing deals, but individual European countries keep their own patent systems for space inventions.

Jurisdiction gets tricky when activities cross legal borders. If a satellite launches from one country but gets operated from another, sorting out IP can get complicated.

Enforcement is also tough internationally. Patent disputes over space tech might end up in several court systems. Companies need to navigate a maze of national rules for IP protection and enforcement.

Space ventures depend on three main types of intellectual property to protect what they invent. Patents cover big breakthroughs like reusable rockets and asteroid mining gear.

Copyrights lock down software and technical documentation that keeps spacecraft running.

Patents are probably the most powerful IP tool for space companies building new tech. SpaceX holds a stack of patents for its Falcon Heavy rockets, and Blue Origin protects its New Shepard propulsion systems the same way.

Some patentable space tech:

Patent protection gets complicated in space, since regular territorial lines don’t really exist up there. Companies often file patents in several countries to cover all their bases.

The Patent Cooperation Treaty helps space firms get patent rights in multiple countries. That’s pretty much a must with space missions crossing borders all the time.

Patent disputes already pop up in the space world. When two companies work on similar satellite tech or spacecraft designs, infringement claims can get messy.

Copyrights protect all the creative and technical stuff that makes space missions work. Software algorithms, mission planning docs, and satellite images all fall under copyright.

Space companies generate loads of copyrightable material. Navigation code for Mars rovers, communication protocols, and maintenance manuals all need copyright protection.

Covered materials:

Copyright ownership gets tangled when multiple countries work together. The International Space Station, for example, brings together partners with different copyright rules.

Commercial space companies need clear contract terms with government agencies. These contracts decide who owns software built for NASA or data from commercial satellite runs.

Trademarks protect brands as space business goes commercial. Virgin Galactic, SpaceX, and Blue Origin all have registered trademarks for their names, logos, and spacecraft models.

Space tourism companies lean hard on trademarks to stand out. Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo and Blue Origin’s New Shepard are both trademarked, so others can’t use those names.

Common space trademarks:

Trademark enforcement in space is a real puzzle—no borders means national trademark systems don’t always fit. Companies have to figure out which country’s rules actually apply.

As we get space hotels, lunar mining, and even Mars colonies, trademark protection will only get more important for building brands off-Earth.

On Earth, intellectual property laws rely on clear national borders and territorial control. Space law flips that on its head, since no nation can own any part of outer space or a celestial body.

Intellectual property rights hit their biggest legal snag when inventions leave Earth’s atmosphere. Traditional patent systems need specific places to decide which country’s law applies.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty calls outer space and celestial bodies the “province of all mankind.” No one can claim sovereignty over the Moon or anything else out there. So, patent laws can’t follow their usual territorial playbook.

Space inventions generally fall into three buckets:

Each category brings its own legal headaches. When astronauts from different countries invent something on the ISS, patent ownership becomes a real puzzle.

Some countries are adapting. The US tweaked its Space Act to allow patents for inventions created or used in space. The European Space Agency built policies for patenting inventions made by ESA staff in space.

The Registration Convention tries to fix jurisdiction issues by tying legal authority to the country that launches and registers a space object. Each nation keeps control over its own spacecraft, gear, and crew.

This sets up a “flag state” system, kind of like maritime law. The country that registers a spacecraft keeps jurisdiction over what happens on board. But companies sometimes register spacecraft in countries with weak IP rules to dodge strict enforcement.

That loophole can really undermine space IP protection.

The International Space Station is a wild example—multiple legal systems run at the same time. Each country runs its own module by its own laws, and when astronauts move between modules, they actually enter different legal jurisdictions.

International organizations play a big part in shaping space intellectual property rules. UNOOSA and WIPO work to set unified standards, while bilateral agreements let nations team up directly.

The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) takes the lead in coordinating international space law. They draft guidelines that help countries sort out intellectual property disputes tied to space activities.

UNOOSA also helps member states swap information about how they cooperate in space. They encourage countries to share how they protect innovations that come out of space missions.

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) zeroes in on IP policy for space technologies. WIPO works to build legal environments that support innovation and protect the rights of inventors.

Key WIPO contributions include:

UNOOSA and WIPO team up to tackle the tricky problem of enforcing IP rights in space. Their joint efforts push for clear standards that help cut down on legal headaches between countries exploring space.

Countries often partner directly to share space technology and protect their joint innovations. For example, the United States and Luxembourg signed agreements that make it easier to develop commercial space resources and safeguard each nation’s IP rights.

Multilateral agreements bring several countries together to chase shared IP goals. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 still serves as the backbone for peaceful space exploration and IP cooperation.

Effective cooperation mechanisms include:

Nations with advanced space programs often collaborate with developing countries to build skills and share know-how. These partnerships make sure IP protection isn’t just for the big players.

Private companies get involved too, especially through public-private partnerships. Commercial ventures need solid IP guidelines before they’ll risk investing in expensive space tech.

Patent laws really struggle to cover inventions that leave Earth’s surface, leading to enforcement gaps. National patent offices like the USPTO have different ideas about extraterrestrial jurisdiction, while international agencies sometimes find coordination tough.

Patents only give rights within a specific country, but space is, well, not anyone’s country. The Outer Space Treaty says no nation can claim space.

This creates a real dilemma. Patent laws are meant to keep others from using your invention without permission, but space law says everyone should have access.

The Registration Convention tries to bridge this gap. Countries keep authority over space objects they register and launch, so patent laws could, in theory, apply to those objects.

The United States is the only country that has clearly extended patent protection to space. Section 105 of Title 35 treats inventions made on US-registered space objects as if they happened on American soil.

Key exceptions exist:

This loophole lets some companies dodge infringement claims by picking registration-friendly countries. Space companies sometimes build patented tech and launch from places with less strict IP protection.

The USPTO leads the way in space patent protection with clear laws. US patent law covers inventions made, used, or sold on US-controlled space objects.

This approach covers most commercial space activities. Companies that launch from the US or use US-registered spacecraft answer to the USPTO.

Other patent offices do things differently. The European Patent Office leaves it up to member states rather than having a single space patent law.

Germany changed its own patent rules before joining International Space Station agreements. Now, German patents apply to European Space Agency-registered objects, but the coverage is still pretty limited.

China and Russia stick with their own patent systems and don’t have specific space rules. Their growing space programs make things tricky for international inventors.

Most countries haven’t created special space patent laws. This patchwork system forces companies to juggle multiple jurisdictions and figure out enforcement on their own.

The European Space Agency works under a complicated multi-national setup. Each member state keeps its own patent system, which can make things messy for joint space missions.

ESA spacecraft often use parts from different countries. Patent disputes can pop up over which country’s laws actually matter for a project.

The International Space Station is probably the best example of space patent coordination. Partners negotiated detailed agreements to define intellectual property rights for each module.

ISRO, India’s space agency, faces its own challenges as the program grows. Indian patent law doesn’t say much about space, so commercial ventures might run into gaps.

International coordination is still pretty limited, even as commercial space activity ramps up. Most agencies handle patent rights through one-on-one agreements instead of big frameworks.

WIPO has looked into space patent issues, but hasn’t set any binding rules. Countries keep coming up with their own ways to protect IP in space.

Private companies have to deal with this patchwork when working on space tech. Filing patents in multiple places is basically a must if they want real protection.

Space missions run under legal frameworks that make enforcing intellectual property rights a real headache. Companies have to figure out which country’s laws apply and set up clear licensing terms for their space inventions.

Trying to enforce IP rights during space missions brings up all sorts of legal puzzles. The biggest issue is jurisdictional ambiguity in space law.

Most countries apply their own patent laws to spacecraft registered under their flag. So, SpaceX missions answer to US patent law, while ESA missions follow member state rules.

Key enforcement challenges include:

Space missions usually set up IP protection through pre-flight agreements. These contracts spell out which country’s laws apply and how to handle violations.

The International Space Station is a good example for IP enforcement. Each module follows the laws of the country that built it. Research in the US segment falls under American patent law, and work in the Russian part uses Russian rules.

Companies working on space tourism need to think about these enforcement setups to protect their inventions. Virgin Galactic’s tech, for instance, gets covered by US law during suborbital flights.

IP disputes in space need special legal handling because everything is so international. Regular courts have a tough time with cross-border enforcement.

Most space companies go for alternative dispute resolution. Arbitration panels with space law experts handle these cases better than standard courts.

The industry is using more specialized arbitration centers now. The Court of Arbitration for Sport has started taking on space-related commercial disputes. These forums know both IP law and the technical side of space.

International treaties don’t offer much help for IP lawsuits. The Outer Space Treaty sets out basic ideas, but doesn’t really tell you how to enforce IP rights.

Recent cases about satellite tech have set some important examples. Courts have to decide if the infringement happened in space or on Earth, which changes which laws apply.

Common dispute resolution methods include:

Commercial space companies usually put mandatory arbitration in their contracts. It’s faster than going to court and keeps things private.

Licensing agreements are the backbone of IP protection for commercial space projects. These contracts need to tackle the weird challenges of operating outside Earth.

Space licensing agreements often include territorial clauses that go way beyond normal geographic limits. Companies have to say if licenses cover Earth orbit, the Moon, or even deeper space.

Standard licensing terms for space applications:

NASA’s commercial crew program is a good example of licensing done right. SpaceX and Boeing license NASA tech but keep rights to their own inventions. These deals clearly lay out who owns what.

Space tourism companies face their own licensing headaches. Virgin Galactic licenses some tech from Scaled Composites but also builds its own systems. These contracts have to cover safety and regulatory details.

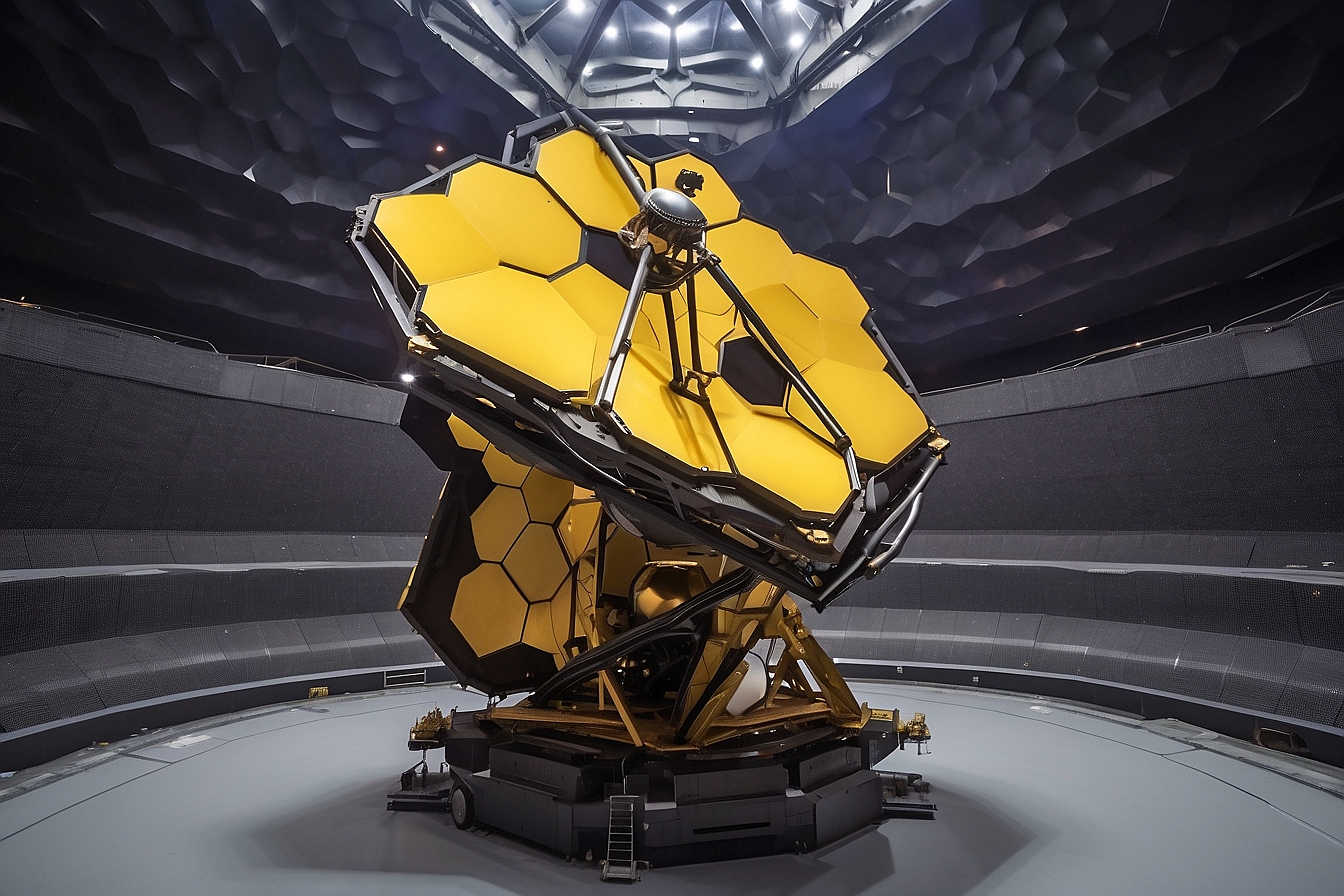

International licensing is a must for big space projects. The James Webb Space Telescope involved complex deals between NASA, ESA, and private companies. Each party kept certain rights while sharing the main tech.

Cross-licensing helps space companies avoid IP fights. Blue Origin and other launch providers sometimes swap patent licenses to make things smoother.

Modern space licensing contracts even look ahead to future tech. Companies try to cover things like space manufacturing and asteroid mining when writing up their IP deals.

Companies building space inventions have to jump through hoops to keep their tech and processes secret. With vast distances and overlapping jurisdictions, protecting confidential info and preventing leaks gets complicated fast.

Space tech companies need strong strategies to keep their secrets safe. Trade secrets in this sector can include manufacturing processes, orbital calculations, propulsion designs, and mission planning algorithms.

Key protection methods:

Companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin keep their engine designs and manufacturing tricks as trade secrets instead of patenting them. This way, they avoid public disclosure and keep protection going as long as they can keep things under wraps.

Space missions with partners from different countries make confidentiality even harder. Companies have to set clear rules for info sharing and access when they collaborate.

Trade secret theft is a real risk in the space industry, given the fierce competition and global nature of the business. Having foreign nationals, government agencies, and lots of contractors around just adds to the challenge.

Effective prevention strategies:

Enforcement gets tricky when someone uses a stolen idea in orbit or on another planet. Companies need to sort out legal jurisdictions and enforcement plans before launching anything valuable.

The fast pace of the space sector means employees often move between companies. Firms have to protect their secrets but also let people change jobs and work with others in the industry.

The commercial space sector has shifted from government-run programs to a booming market worth hundreds of billions. Private companies now drive innovation in satellites, missions, and all sorts of new commercial uses that are changing how we access space.

The space economy has exploded in the last decade. US patent applications for space tech jumped 144% since 2003, way outpacing the 37% growth in other tech areas.

Key Growth Drivers:

The space economy now covers way more than just rockets. Earth observation, communications, and navigation services pull in big money. Space tourism companies are gearing up to send regular folks to suborbital and orbital destinations.

Investors seem excited about commercial space. Private funding keeps breaking records as companies roll out new satellite constellations and get ready for deeper space missions.

Satellite technology drives most commercial space activity these days. Companies want to protect their breakthroughs, so they file patents for new designs, clever software, and manufacturing tricks.

Protected Technologies Include:

Companies enforce satellite technology patents mostly during manufacturing and operations on Earth. They guard their thruster designs in the factory and defend software patents when processing satellite data at ground stations.

Commercial satellite operators face some pretty unique IP headaches. Once a satellite reaches orbit, it’s literally outside any country’s borders. The US tries to handle this by extending patent law to inventions on US-registered space objects.

IP Strategy Considerations:

NASA’s commercial crew program is a solid example of public-private collaboration. NASA teams up with SpaceX and Boeing to send astronauts to space, which opens new markets and helps cut government spending.

Private companies move quickly and aren’t afraid to take risks. SpaceX, for example, built reusable rockets by pouring in private investment and running lots of tests.

Government agencies set the rules and give the first big contracts. NASA buys commercial launch services, which gives private companies steady income. The Federal Aviation Administration handles licensing for commercial space launches.

Partnership Benefits:

Space tourism companies stand on decades of government experience. They adapt old tech for civilians and design new safety systems and training. This teamwork is starting to let paying customers, not just astronauts, reach space.

Space mining and using resources from space are growing fast. Intellectual property protection is turning into a must-have for companies hoping to succeed. Firms are building extraction technologies and trying to figure out the legal mess around who owns what and how to keep their inventions safe.

Space resource utilization means extracting and processing stuff from asteroids, the Moon, and maybe even Mars. Water, rare minerals, and platinum-group metals are the big prizes.

The legal side is, well, complicated. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 says celestial bodies belong to everyone. But the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015 lets companies own what they dig up.

Key intellectual property challenges include:

Companies need patents for mining equipment, processing methods, and robotic systems. These usually involve advanced propulsion for moving spacecraft and automated systems for mining.

The rise of in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) adds more IP questions. ISRU systems turn raw space materials into products right where they’re found, cutting costs and making long-term operations possible.

A handful of companies are leading the way in space mining. Each one focuses on a different piece of the puzzle.

Leading space mining companies:

| Company | Focus Area | Key Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Planetary Resources | Asteroid mining | Prospecting satellites, robotic systems |

| Deep Space Industries | Resource processing | ISRU equipment, propulsion systems |

| Moon Express | Lunar operations | Landing systems, extraction tools |

Planetary Resources builds spacecraft for finding and identifying asteroid resources. They use advanced sensors and robots built for zero gravity.

Deep Space Industries zeroes in on processing tech and propulsion. Their ISRU gear turns raw materials into fuel and building supplies for space use.

Robotic automation is huge here. Companies patent autonomous drills, processing equipment, and navigation systems. These let them run mining ops remotely in tough environments.

Advanced propulsion keeps mining spacecraft on target and moves resources around. Ion drives and chemical engines need special designs for long-term space work.

NASA backs space mining through partnerships and research. The Artemis program includes resource utilization for building lunar bases and making fuel.

NASA partners with private companies to develop extraction tech. This mix of government know-how and commercial innovation pushes mining capabilities forward.

Current mission developments:

Other space agencies are getting involved, too. The European Space Agency is looking at lunar resources to support Mars missions. Japan and India are building extraction tech through their own programs.

Commercial missions aim to prove extraction is possible. Companies run small tests to show their tech works before investing more. These missions generate valuable IP as teams learn and improve their methods.

Regulators are trying to set up clear rules for space mining. The Federal Aviation Administration handles launch oversight, while other agencies look at resource ownership and environmental issues.

The space industry faces tough choices about how to protect inventions and stay ahead as more players enter the scene. Legal frameworks are shifting as commercial space ventures grow beyond traditional government missions.

Private companies are changing how space exploration handles intellectual property. SpaceX’s reusable rockets show how smart patent portfolios can give a company an edge. Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic are doing something similar, locking down patents on engines and vehicle designs.

Now, a lot of commercial space tech stays under wraps as trade secrets instead of becoming public patents. Companies protect key algorithms for debris avoidance and navigation by using confidentiality agreements. It’s a sign of how competitive things have become.

AI is starting to transform IP management. Automated systems now track possible patent violations in real time. Some companies use blockchain to keep IP ownership records safe and clear between partners.

Big players are starting to cross-license. They share non-core tech but keep their crown jewels private. This speeds up space exploration by cutting down on duplicate research.

Satellite constellations bring new IP headaches, like who gets which orbital slots and frequency rights. Regulators are scrambling to keep up with these new challenges.

Countries are working together more to align space IP laws. The World Intellectual Property Organization is building frameworks to answer tough questions about who owns what when inventions happen in space.

Patent law is shifting to cover space-specific issues, like manufacturing in zero gravity or mining asteroids. Courts are starting to set rules for inventions developed across multiple locations—on Earth and in orbit.

Space technology transfer rules between government and private companies are getting an overhaul. New policies try to balance national security with the need for innovation. Licensing is getting faster to keep up with urgent missions.

As asteroid mining gets closer to reality, new rules for resource rights are coming. These laws will shape how companies claim ownership of what they extract in space.

Data rights are evolving, too. With more sensors and communication satellites, privacy rules are stretching beyond Earth as space-based internet expands.

Space intellectual property law is a mix of international treaties, national patents, and new commercial agreements. These systems try to protect inventions in space, but they also have to handle tricky questions about enforcement, NASA’s big portfolio, and who’s in charge when things happen off Earth.

Several legal systems cover intellectual property in space. It all starts with international treaties like the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which lays out ground rules for space activities.

National patent laws apply to citizens and companies from each country, even when they’re working in space. The US uses its Patent Act, and Europe follows the European Patent Convention. These protect inventions by their nationals, no matter where they’re made.

The World Intellectual Property Organization offers more guidance through global agreements. The TRIPS Agreement from the World Trade Organization also shapes how countries handle space IP.

NASA uses Space Act Agreements to set specific IP rules with private partners. These agreements spell out who owns tech developed in public-private collaborations for space projects.

The Outer Space Treaty makes patent enforcement really tough because it bans any nation from claiming space as its own. Without territory, it’s hard to say whose patent laws apply.

The treaty calls outer space the “province of all mankind,” which doesn’t fit well with exclusive patent rights. So, it gets confusing when patent disputes pop up on spacecraft or stations.

Patent holders run into problems enforcing rights, since no clear international court has authority over space. Companies have to use Earth-based courts, even if the alleged infringement happened in orbit.

The International Space Station has a special setup—each module follows the laws of the country that built it. That helps a bit, but there are still gaps for activities outside those zones.

Yes, companies file patents for space tech through their home countries. SpaceX owns lots of patents for its reusable rockets, and Blue Origin has patented various spacecraft systems.

Patent applications for space inventions follow the same rules as those on Earth. The invention must be new, non-obvious, and useful. Many patents cover engines, life support, and communication tech.

Private space companies work hard to build up patent portfolios to defend their R&D investments. These patents cover tech used or built on Earth, even if it’s meant for space.

Some countries updated their laws so astronauts can patent inventions made in space. In the US, astronauts can file for patents after space missions, and the rights follow the usual process.

Jurisdiction is the biggest headache for enforcing IP in space. Different spacecraft might be under different national laws, which makes it unclear whose legal system should handle disputes.

Collecting evidence is another problem. If a patent gets infringed on a spacecraft, it’s tough for courts to inspect the tech or get testimony from people in orbit.

International cooperation is necessary but complicated. The ISS requires coordination between American, Russian, European, and other legal systems when IP issues come up.

Emergencies can make things even messier. If a crew needs to use patented tech to stay safe, the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts suggests safety comes before patent rights.

Patent protection on the Moon or elsewhere is still a legal gray area. The Moon Agreement of 1979 says celestial bodies are the “common heritage of mankind,” which doesn’t sit well with exclusive rights.

Most countries haven’t signed the Moon Agreement, so their own patent laws still apply to space activities. American companies, for example, might enforce their patents on the Moon if Americans are involved.

Actually enforcing patents on the Moon is a huge challenge—there’s no court system or legal infrastructure there. No one is issuing injunctions or handling disputes on lunar soil.

Future mining missions will probably push these legal limits. Companies are already filing patents for extraction and processing tech and are hoping their home countries will protect those rights beyond Earth.

NASA takes a pretty active approach to developing and protecting its intellectual property. The Strategic Partnerships Office leads the way, filing patents for new tech that NASA researchers come up with.

They don’t just sit on these patents, either. NASA works to license these innovations to private companies, hoping someone out there will turn them into something useful for the world.

The agency actually holds thousands of patents. Seriously, they’ve covered everything from spacecraft designs to materials science.

Their patents touch on propulsion, life support systems, communications, and all sorts of scientific instruments. Most of these were first created for space missions but have potential back here on Earth too.

When NASA teams up with private partners, they use Space Act Agreements. These agreements spell out who owns what when it comes to intellectual property.

Usually, NASA keeps the rights to the tech it develops. Partners get the rights to their own inventions, which seems fair enough.

NASA tries to balance protecting its patents with its public mission. By licensing out technologies for commercial use, they encourage more innovation.

It’s a way to make sure taxpayer-funded research doesn’t just sit on a shelf. Through technology transfer programs, NASA helps bring those discoveries into the broader economy.